- Technology that enabled social distancing and promoted public health during the pandemic, also helped to improve work-life integration.

- Now that we have this technology and virtual ways of doing things, we should continue to use it to sustain work-life integration in the future.

At the time of this post, the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted 188 countries, with 4.5 million confirmed cases worldwide and more than 300,000 deaths. Families are mourning, businesses are filing for bankruptcy, and those who have not yet suffered tangible loss are overwhelmed with fear and unanswered questions. As physicians and members of the health care workforce, we are smack-dab in the middle of it all—juggling care of the sickest COVID patients and managing non-COVID patients in a resource-limited world, while also trying to guide our communities, educate the public, and protect our families despite our heightened exposure. This is a tough time, to say the least, but is it possible that some good byproducts have arisen from the ashes of this disaster?

I would argue that yes, work-life integration has changed for the better and in ways that I hope can be sustained for the long haul.

As clinicians, many of us have little relatability to the general public’s sense of boredom and cabin fever. Our status as “essential workers” has kept us busy, albeit to various extents in every region and specialty. However, despite my ongoing clinical, academic, and administrative obligations, my commitments outside of work have looked completely different. As parents of four healthy and energetic children, my husband and I are accustomed to running from place to place all the time. Somehow, we manage carpools with four kids at three schools, hockey, gymnastics, cheerleading, figure skating, tennis, choir concerts, not to mention playdates, birthday parties, school meetings, and the occasional opportunity for our own social lives. With both of us having demanding careers requiring substantial travel and early morning as well as evening meetings, we often functioned like passing ships in the night (loaded with cargo of car seats, ice skates, pompoms, and laptops). On the rare occasion that we had four, five, or somehow even all six of us available for an hour or more, there was pressure to “do something”—make a dinner reservation, buy tickets for an exhibit, plan an event with another family. And then, in March 2020, almost overnight, everything came to a grinding halt.

Yes, as a surgeon, I have continued to be “busy” with my job—but there has been no travel to the last three conferences that I was slated to attend. There have been no sports practices, no family vacations, and no places to take our kids. And, thus, we have had so much opportunity to spend time together in the most simple of ways. While I’m still working, many of our evenings and weekends are free. Our two digital family calendars and our dry-erase calendar in the kitchen no longer describe places to go; they are now populated with Zoom links for distance-learning classes and dinner menus. In this simple pace of life, we have found so many new ways to enjoy time together. It took a pandemic for me to get on my bicycle for the first time in a decade, and now family bike rides occur several times a week. To make up for my daughter’s missed choir trip to New York, we had a New York-themed dinner, incorporating attire, a music play list, décor, and a menu to make her feel like she’d gone to New York. Weekly themed dinners are now a regular activity in our house: a luau, stadium night, and there will be a fifth-grade graduation night. In some ways, we are reminding ourselves of the things that we miss and that we used to do, but we are also enjoying each other’s company in inexpensive, innovative, and fun ways. We are spending inordinate amounts of time together, appreciating each other more than ever.

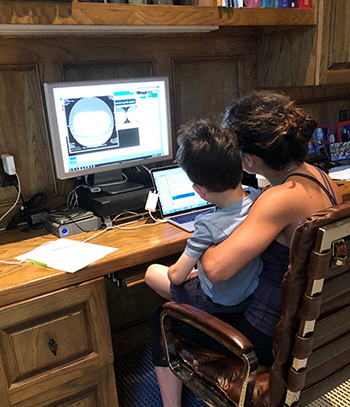

Even during “working hours,” I have seen much more of my family. Prior to the pandemic, I typically had 1.5 days of clinic per week, 2-3 days of operating, and the rest of the time was filled with administrative activities, research, and trainee education. In recent weeks, I have had far fewer operations to perform, and my in-person clinics have been shorter, as appointments have either been converted to telemedicine or delayed. Most substantially, every single meeting that I routinely attend has been converted to a virtual environment—every tumor board, research conference, M&M, committee meetings, mentoring engagements, multidisciplinary collaborations, and more. For these reasons, despite having similar work obligations, I have found myself working from home—either on telemedicine or tele-meetings—for several hours every day, with my time in the hospital limited to literally just performing operations, seeing clinic patients, and rounding. And, naturally, with all this extra time at home, I’m seeing much more of my family. To be clear, this doesn’t mean that I’m substituting work that I should be doing for taking care of my kids. But instead of taking 10 minutes to stand in line to buy coffee that I drink alone while walking from my office to the hospital, I brew a pot in my kitchen while tickling my 4-year-old and asking my 10-year-old about his distance learning for the day. Instead of scarfing down lunch alone in the cafeteria, I go on a bike ride with my 12-year-old. And instead of FaceTiming my 2-year-old from my office to say goodnight between evening meetings, I can use the same time to rock her and tuck her in myself. Being able to hug my kids, share meals with them, and have them interrupt me with a million questions in-person rather than via text message—these moments are amazing gifts that I do not take for granted.

These changes were not made to improve work-life integration; they were made to enable social distancing and promote public health. But the impact on family has been immense.

Like our employers, many other organizations have had to change their ways during times of social distancing. Case in point: middle-school orientation. One year ago, I skipped tumor board and our weekly departmental research meeting in order to take my oldest daughter to a crowded middle school. We heard about a day in the life of a sixth-grader, learned about various electives, and filled out her course selection forms. It was a madhouse. Fast forward a year and was my oldest son’s turn. Instead of skipping any meetings, I found a time that worked for both me and my son. We went on a walk while we navigated the sixth-grade orientation website from my phone. We watched all the videos from the teachers and the students and filled out a Google-form with his course selection. It was great bonding for the two of us, with no crowds or skipped meetings, and it was personalized (we didn’t watch the videos for the orchestra or hip-hop electives, because he wasn’t remotely interested). So, as we consider that there are ways to keep remote options available for our academic, educational, and administrative meetings, how wonderful would it be if the other parts of our lives kept remote options available for working parents?

As surgeons and healthcare providers, we are incredibly fortunate to make an impact in people’s lives and those of their families every single day. We are rewarded with relative job security, praise, and respect. Our jobs are essential, and we couldn’t do them without the support of partners, family, and friends. And, at the end of the day, the reason why we do it is because our patients are “somebody’s family.” Let us not forget the importance of our own family in all of this. I am grateful for these extra opportunities to be with my family—while brewing coffee, while biking, and even while filling out Google forms. As families are suffering and grieving worldwide, I thank my lucky stars for the blessing of health for those whom I love. Let’s not forget the lessons learned in this time. We have the technology, we have the Zoom links, let’s not delete them. We have achieved, at last, work-life integration. Let’s keep it for good.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Society of Thoracic Surgeons.